A parade of fund managers, showing both their eclectic viewpoints and love of the United States and its capitalist system

Last month we claimed that the same stocks are often held by the same funds. But we didn’t back it up with any data.

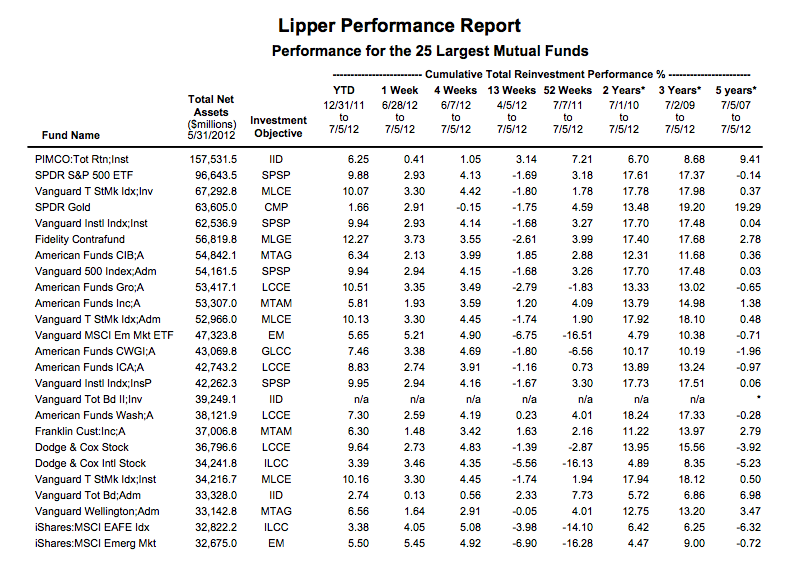

Lipper is the go-to company for fund research. This is their list of the largest mutual funds by net assets. Let’s walk through the relevant abbreviations and codes.

The 3rd column lists the funds’ objectives.

IID is intermediate investment-grade debt. “Intermediate” refers to the length of the debt, 5 to 10 years.

SPSP means the fund is supposed to replicate what the S&P 500 does.

MLCE is multi-cap core funds. “Multi-cap” means the fund invests in a range of market capitalization sizes; everything from giant companies to small ones, with no more than ¾ of its value in any one size. If you want that size quantified, well, you’re asking too many questions. (That’s not a copout. We seriously couldn’t find a formal definition.)

CMP is commodities precious metals, which means not just physical gold and silver, etc., but their corresponding derivatives.

MLGE is multi-cap growth funds. Same as MLCE, except MLGE funds invest in stocks with above-average price-to-earnings ratios, price-to-book ratios and 3-year sales-per-share growth value.

We’ll spare you the rest of them – if you want the details, they’re here – but now we’ve got 3 categories (SPSP, MLCE and MLGE) that specialize in equities, as opposed to debt or commodities.

Here are the biggest holdings of the SPDR S&P 500, the largest S&P 500 replicator:

Apple 4.66

Exxon Mobil 3.26

Microsoft 1.81

IBM 1.76

General Electric 1.72

AT&T 1.71

Chevron 1.71

Johnson & Johnson 1.54

Wells Fargo 1.46

Coca-Cola 1.44

Here are the largest of the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund, the largest multi-cap core fund and one whose very summary says it’s “designed to provide investors with exposure to the entire U.S. equity market, including small-, mid-, and large-cap growth and value stocks.”

1 | Apple | |

2 | Exxon Mobil | |

3 | Microsoft | |

4 | IBM | |

5 | AT&T | |

6 | General Electric | |

7 | Chevron | |

8 | Procter & Gamble | |

9 | Johnson & Johnson | |

10 | Pfizer |

Wow, what tremendous diversity. Did you notice how although the two funds’ 1st– through 4th– and 7th-largest components are the same companies in the same order, the one fund’s 5th-biggest component is AT&T and 6th-biggest is GE, while the other’s 6th-biggest is AT&T and 5th-biggest is GE? It’s like they’re from different galaxies!

Finally the Fidelity Contrafund, the biggest multi-cap growth fund. It holds the stocks of, according to Fidelity, “companies whose value (we believe) is not fully recognized by the public.

| APPLE |

| BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY |

| MCDONALDS |

| COCA-COLA |

| WELLS FARGO |

| NOBLE ENERGY |

| TJX COMPANIES |

| WALT DISNEY |

| NIKE |

Apple’s value could not be more recognized by the public if the company tattooed its logo on every citizen’s forehead. Same with Google. The only Contrafund major component that you might not have heard of is Noble Energy, a $7 billion oil and gas driller based out of Houston.

Funds make their full holding data difficult to access. Contrafund has 413 components (which is nothing compared to the Vanguard fund, which has 3220 components.) The Fidelity fund’s components are listed here. We can’t put an image in the site, it’d run for way too many columns, but here’s a summary:

Microsoft is 50th on the list. The Contrafund’s 2nd-biggest component, Google, is 13th on the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund list while Berkshire Hathaway is 36th, McDonald’s is 25th, Coca-Cola is 15th, Wells Fargo is 11th and Disney is 33rd.

It doesn’t matter whether you do business with Fidelity, with Vanguard, with American Funds or with PIMCO. Buy a mutual fund, at least one that deals in equities, and you’re paying a fund manager to say “Hmm…this Apple looks like a good buy. I think I’ll pick some up.”

Look, this isn’t necessarily an argument for you to stop whatever your occupation is and devote the requisite hours to becoming an amateur fund manager. Whatever motivates you. Rather, we’re asking you to acknowledge that “picking” hundreds of stocks en masse barely counts as picking. Choosing the stocks of the largest, most profitable, most widely held companies doesn’t take any special aptitude or knowledge. It’s a defensive measure, done purely out of the fund manager’s self-interest. He’s thinking:

I’m 20-something. I’m making ridiculous money, way out of proportion to the value I’m creating. Women are enamored of me, or at least of what I can buy. Should I actually do some research, look for nothing but undervalued stocks (which there won’t be 413 of, at least not simultaneously), sell all of my fund’s current components and buy those instead?

Of course not. The higher-ups wouldn’t have it. They’d have me, roasting on a spit. My job isn’t to provide the highest possible returns. It’s to avoid mistakes.

Understand that there is no room for outliers nor independent thinkers among the ranks of the major fund managers. The managers’ job is to be as conservative as possible. Which means your money is going to be treated conservatively, which means little chance for legitimately large appreciation. When a fund hits big returns, it’s an accident. Yes, there’s a top-performing fund, and a top 10 list. Every year and every quarter. There has to be. Someone’s got to be at the top. Whether the SPDR S&P 500 outperforms the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund thus reduces to little more than the question of whether AT&T will outperform GE.

You can do better than this. You can also do worse, but we’re talking to the ambitious among you.

Synthesizing the classical proverb with Mark Twain’s updating of it, “Put your eggs in a few baskets. And watch those baskets.” You need to buy individual stocks. You can start by reading here.