You’ve probably heard the expression, “You don’t get what you deserve. You get what you negotiate.” Okay, who coined it?

- Zig Ziglar

- Og Mandino

- Yag Oliveri

- Tom Peters

- Chester L. Karrass

1, 2 and 4 are/were self-help authors and motivational speakers. 3 is a name we made up.

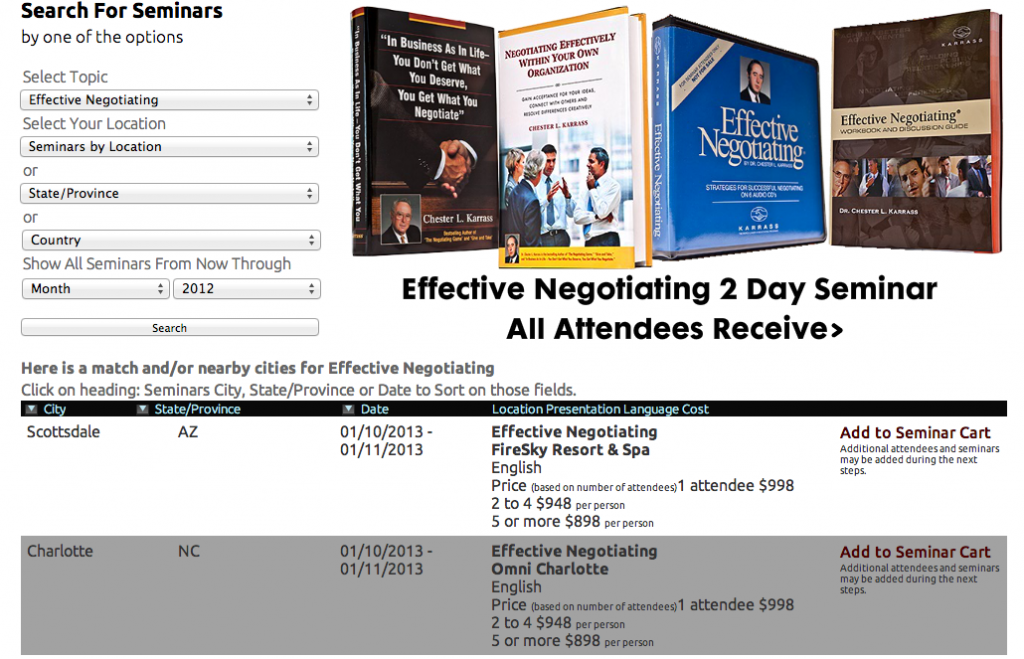

5 is the right answer. You might remember him from such SkyMall ads as The Karrass Effective Negotiating Seminar. He’s this dour yet confident man:

He might not even exist. Biographical information on Mr. Karrass is sketchy, but if he’s alive it seems he’s 89. That seems to be the most recent picture of him, and it looks to be at least 30 years old. Anyhow, Chet fancies himself as the authority on negotiating. Sit through one of his seminars and you’ll learn how not to leave money on the table, and how to make your adversary weep and gnash his teeth while you bleed him dry and leave a desiccated carcass where a would-be negotiator used to be.

The first rule of negotiation, as we all know? Get a number out of the other person first. Oh, you want my car? How badly? (Or conversely, You want to sell me your car? How badly?) It doesn’t matter how long the standoff (or standstill. Standoff? Standstill) lasts. Wait, wait, wait until the other party mentions a number, out of sheer boredom if nothing else. At that point, he’s already ceded tremendous ground.

What if you’ve both heard this rule and taken it to heart? Then stand there staring at each other until the 7th Seal is broken, whatever. This can’t happen in real life, only in theory, because at one point one party will say “This stalemate is eating up so much of my time that I need to be compensated for it. I quit. Either that or I’m internally recalibrating the scale and raising/lowering my price.”

Exchanging a car is the classic example, because it seems everyone does it sooner or later and the market itself is relatively unencumbered by regulation. And it usually involves head-to-head confrontation between the parties. But regardless of what good or service you’re exchanging, the rule applies. Get a number before you give one.

Here’s the funny part.

Q: How much does it cost to sit through a Karrass seminar?

A: Exactly what they tell you it’s going to cost, Ace. Take it or leave it.

Now if you spend $1000 (excuse us, a much more reasonable $998) on a seminar, are you getting the best possible deal? Or are you on the receiving end of something one-sided?

You’re not negotiating, at any rate. Furthermore, the folks at Karrass seem to be violating the first rule of negotiating themselves. So what gives? Is everything we think we know a lie?

The Karrass people would argue that you have to be practical, it would grind their business to a halt if they had to haggle over every single transaction. The Control Your Cash people would argue that if you take the other party’s first offer, you’re paying too much.

You don’t need to drop a grand (or $900, if you can find 4 friends with too much money) to learn how to negotiate. You just need to develop a backbone. Learn to walk away. It’s this compulsion to make a deal, any deal, that leads to awful decisions. Even in the non-economic realm. Just ask the lonely guy who does everything but get down on his knees and beg a woman to go out with him because darn it, we were meant to be together. (Or less commonly, the girl who wants the abusive but occasionally charming guy to take her back.)

After you’ve bought several hundred copies of The Greatest Personal Finance Book Ever Written (complete with details on how to negotiate!) check out this 1997 release by sports agent Mark Shapiro, The Power of Nice. Don’t be fooled by the title, he’s still an attorney and thus probably an awful human being, but the book does contain one exercise that perfectly illustrates what we’re talking about.

Reciting the exercise from memory, you’re supposed to find a partner and each read one side of a page that describes financial details of a potential real estate deal, then negotiate said deal. One person, the seller, reads that he should sell the property in question for somewhere around $2 million, with a little wiggle room. Meanwhile, the buyer reads that he shouldn’t offer much more than $300,000 if he can help it.

The interesting thing is that the negotiated price is almost never around $1,150,000. Inevitably, it’s either close to $400,000, or close to $2,900,000. One party does almost all the conceding.

So don’t be that person. Easy, isn’t it? Lowball profusely if you’re the buyer, ask for something on the verge of absurdity if you’re the seller. Whether it’s a salary, a physical good, whatever. There’s an inherent reluctance to do this, for fear of insulting the other party or not having him take you seriously. Get over this. There are an infinite number of deals to be made, and only a small thinker thinks “I have to make this deal, no matter what.” Being dictated to is no way to build wealth.