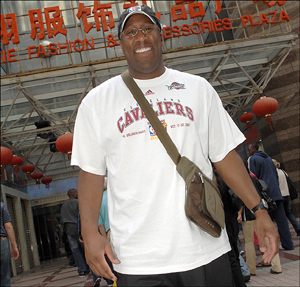

Mike Brown, who coached the Cleveland Cavaliers for 5 years. He won 272 games, lost 138, and in 2009-10 led Cleveland to the best record in the league. Dan Gilbert rewarded him for his loyalty with a pink slip. (Or maybe Gilbert fired Brown for carrying a purse, which we would enthusiastically support.)

We love to rail against corporate slavery here, the explicit message being that if you really enjoy your job and concomitant station in life, have at it. But you probably don’t, and instead of whining about it you should take a chance. Or just wait a few decades and regret it, but it’s up to you.

Here, we’ll let commenter Monica explain it:

As a former hourly employee of a business that made it nearly impossible to leave on time, didn’t pay overtime wages, and expected work to be done at home, this article reminded me of why I took a risk and quit. I swallowed my pride, didn’t complain, and stuck it out to help my family. I have a strong work ethic and would never consider giving less than 100% at my job. After four years of dedication, excellent work and client reviews and awards, I received… wait for it.. a card and a cupcake when I left. I think many people find that companies are far less invested in their employees and seem less inclined to reward them for good work and loyalty. It is a shame because recognition and appreciation encourage employee productivity and longevity. Just my opinion…

People confuse “loyalty” with “honor”. They’re not synonyms. Honor means that you owe your employer whatever you agreed to as conditions of the job. Don’t cut out at 4:30 if the workday ends at 5:00.

If the workday starts at 9 and you get there at 8:15 in the hopes that someone influential notices, what have you proven? Here, we’ll do it in the form of a patented Control Your Cash multiple-choice test:

__That they should think of you the next time a promotion comes up.

__That they can throw extra work at you, maybe so much so that they can even save themselves the trouble of hiring an additional person.

As for loyalty, that’s a faithfulness you have to a family, a spouse, a country. Those are entities that you (presumably) share a goal with. Loyalty to an employer is a falsehood. Among other reasons, because you have different goals:

Your goal is to facilitate your career: your employer’s is not. Your employer’s goal is to turn as big a profit as possible. The two goals might overlap somewhat, but that’s not your employer’s concern.

Employers know this. They understand that it’s human nature to not question authority. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t question your elected representatives (which, many of us seem to forget, are our employees.) Far from it. It means you should question your employer if you’re expected to do something beyond what you’ve agreed to. And that you shouldn’t succumb to pressure to do otherwise.

Telling most people to stand up for themselves is like telling a newborn baby to go to the store and run some errands, but we’ll continue.

We’ve had a year to put the following illustration of this in perspective. Last July, after 7 years of Hall of Fame-worthy play as a Cleveland Cavalier, a young multimillionaire named LeBron James exercised his ***RIGHT *** to file for free agency. The terms of his employment explicitly allowed this. He owed it to himself to exercise this right. Not doing so would be like taking only 2 weeks of vacation despite being allowed 3.

Even if you’re not a basketball fan, you probably know what happened next. James signed with a conference rival, and became as hated in Cleveland as Benjamin Netanyahu is in Gaza.

Millions characterized James leaving town as “betrayal.” You know, because wanting to find a new basketball team to play for is the equivalent of condemning The Savior of Mankind to a grisly death for 30 pieces of silver.

James irreparably severed his relationship with the idiot basketball fans of Cleveland, but that’s not the point. We can’t expect them to act rationally, and besides, they had no skin in this game. James’s employer/employee relationship, on the other hand, went to strange new places.

His now-former employer, billionaire Dan Gilbert, violated the Universal Boss Code. In a stunning display of childishness he exposed his feelings and let the world know that in his eyes, James’s only value as a human was in the difference he made to his, Gilbert’s, bottom line. For good measure, Gilbert added “selfish”, “heartless”, “callous”, and “cowardly” to his list of adjectives. Gilbert went way past infantile, reducing the prices of James-themed merchandise to $17.41 (in pennies, the year of Benedict Arnold’s birth.)

James earned $62 million in salary during his tenure under Gilbert, which means Gilbert must have profited by at least that much by having James around.

Substitute your own name for James’s above, your employer’s for Gilbert’s, and whatever you’ve earned for James’s salary (if it’s at least $62 million, kudos.)

Clearly whatever profits Gilbert was enjoying by keeping James around were worth holding onto. Otherwise Gilbert wouldn’t have worked so hard to keep James in Cleveland, and reacted so impetuously when James exposed a crucial truth: there are limits to a boss’s power. A smart employee can transcend those limits. This particular boss was willing to embarrass himself, in order to keep a valuable employee who understood his own worth in the marketplace. You can expect your own employer to harbor similar feelings if you start being cognizant of your own worth.

If you do, your employer will have to pay you more, accommodate your wishes, make your life a little easier. No employer will do this willingly, and most will start the negotiations by belittling you and making you doubt yourself. The idea of a self-aware employee scares most employers more than an audit does.

Did James sign elsewhere specifically to irk Gilbert? No, that was an ancillary benefit.

Presumably, you have at least a few professional non-monetary goals. James did, and like most pro athletes his include a world championship. He was already making huge money, and would continue to regardless of where he signed. Therefore, other aspects of his job became important. Exercising his right to free agency (which, by the way, you have too), he chose to work for an employer who lured him away by:

- conducting operations in a beautiful city with a perfect climate, as opposed to the rusty chill of Cleveland

- taking the idea of winning a championship seriously, by assembling a roster that didn’t consist of 11 stiffs.

James might have won a title in Cleveland had he stuck around long enough. But he came as close to winning one in his first year in Miami as he did in 7 years in Cleveland, advancing to the NBA Finals and taking it to 6 games. And he didn’t freeze half the year while doing it.

Meanwhile, James’s former team set a record by losing 26 consecutive games. James’s departure cost the Cavaliers an additional loss every other game. Maybe the Miami Heat got a bargain.

An elite financial engine like LeBron James can find himself a better situation. There’s no reason you can’t too.

**This article is featured in the Best of Money Carnival #122**

**This article is featured in the Totally Money Blog Carnival Celebrity Roast Edition**