San Diego? No. Prices are too high and California is a test kitchen of awful laws.

Sharon, Massachusetts (Money magazine’s top place to live)? Similarly restrictive laws, with the added benefit of cold weather. Also, you’d be surrounded by Massholes.

San Francisco? “What’s this foul-smelling squishy thing I just stepped in? Why, it’s a homeless person. Yeah, another one. We’ve been walking on an unbroken carpet of them all the way from Fisherman’s Wharf. I hope the hypodermic needle that last one stabbed me with is at least infected with a treatable strain of hepatitis.”

Louisville, Colorado (also on Money’s list)? No offense, but we’ve never heard of you.

Money and common knowledge are idiots. Here’s our list, the definitive one. We’ll do them in ascending order, add to the drama. Presenting the 5 Best Places To Live in America:

5. An apartment you’re renting.

It’s not like we haven’t said this before, repetition being endemic to personal finance blogging, but every dollar you spend here is a waste. Think about the way this transaction works:

You: Hi! Here’s 1/4, maybe 1/3 of my gross income.

Landlord: Thanks. Here’s a floor. Oh, and I still get to keep it. I also get to keep your money.

You’re an adult, right? Then buy a house. Or at least a townhome or a condo. One more time: this is about building wealth. While wealth doesn’t drop out of the sky, at least for most people, it also doesn’t grow of its own accord. You need to start with the raw material, i.e. some amount of money, before you can do anything with, i.e. invest it. Renting, and thus forking over a big chunk of that investable money, handicaps you from the start. You have to live somewhere anyway, so why wouldn’t you build equity while doing so? Renting is a great way to enrich someone else.

Yeah, let’s hear it. “The housing market crashed and people got foreclosed upon. Why should I let those greedy mortgage companies have another opportunity to profit off my hide?”

The only people who got hurt by the housing “crisis”, which is now over, were those who were in over their heads in the first place. They bought too much house, they crossed their fingers in hopes of appreciation, and plenty of them lied about their income on their applications. (Just the same, those overmatched borrowers should probably blame the lending agents for believing their lies in the first place. Nothing is ever anyone’s own fault.) Being in over your head with anything, whether house payments, student loans or credit card debt is beyond the scope of this site anyway. Go join the other hand-wringers at the more querulous blogs if finding commiseration is more important to you than being rich is.

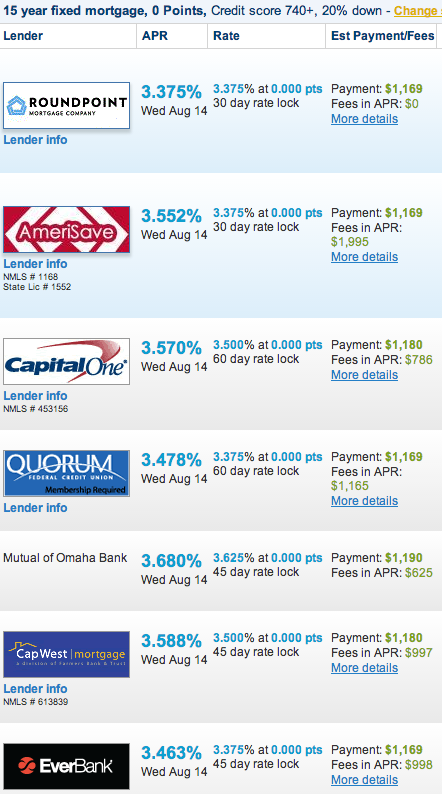

After a 4-year double nadir, prices and mortgage rates are finally rising but still historically low. You can use that as an excuse for not buying if you want, or you can see it as the tremendous opportunity it is.

No, you can’t afford a house when you begin the transition from student to wage-earner. Renting is an unfortunate necessity for most of us at some point in our lives. That point should be as early as possible. Save like your life depends on it – or your livelihood, which it does – until you’ve got enough for a down payment. Once you do, and if you’re motivated enough it shouldn’t take more than a few months, a standard monthly mortgage payment won’t be much more than what you’d otherwise pay in rent. And even if it is, you’re building wealth. Even in a bad-case scenario in which your home doesn’t appreciate as much as you’d like. Your house isn’t going to lose 100% of its value unless you live in Detroit. Your rent payment will lose 100% of its value every single time.

That is, unless you choose

4. An apartment you’ve signed a lease option for.

A lease option. It’s like an ordinary lease, except that at the end of the term you have the option (not the obligation) to buy the property. Lease option renters love this because they think that they’re building toward something, unlike the poor folks under item No. 5. Lease option holders are indeed in a better position than those who have no hope of buying their residences, but…

Care to guess how many lease option holders actually exercise the option? Here’s a quote from Maggie Hawk, who sells real estate in east-central Florida:

In 18 years selling real estate, I’ve never seen it happen.

Renters, by and large, embody certain characteristics. If you smoke, buy lottery tickets, own a pit bull, have a neck tattoo, have ever paid for a UFC pay-per-view, and/or have a couple of DUIs and should’ve walked on one of them but your lawyer screwed you over, it’s far more likely that you rent than own. If you hold a lease option you might think that by the end of the term you’ll have enough wherewithal to buy the place and take advantage of an unsuspecting landlord, but the real world shows a glaring paucity of such renters. Should you be disciplined enough to be one of the few renters who can capitalize on a lease option, you’ll do fine. And will eventually leapfrog over No. 3:

3. An apartment you’re sharing.

Life is going to have financially unhappy episodes. The idea is to compress them into as short a time as possible. If you’re dumb enough to have incurred credit card debt, paying it off in 9 months is always going to be better than just making one more splurge and then ending up taking 18 months to pay it off. Debt bloggers and the staff at MSN Money either don’t know or won’t acknowledge this, but that’s their problem.

Having roommates blows unless you’re one of those odd extroverted people who actually enjoy others’ company more than their own privacy, but again, it’s about minimizing the duration of the pain. Paying half or a third of the rent instead of all the rent means you’ll be on the road to No. 2 all the more quickly:

2. Your own home.

Congratulations. This is where it leads to. Read again from the top if you’re unclear. Equity buildup. Mortgage interest deductions. No matter how much you choose to insist that the glass is half-empty, and that renters are blessed because they don’t have to spend money on everything from landscaping to basic home repair, it’s hard to find a valid counterargument to the point that rent always gives a return of 0.

1. Your own 2nd home.

No one said you had to stop at one. Find a renter – God knows there are enough of them – and you can solve your residential cash flow deficiency easily. Repeat as necessary, and passive income goes from a nebulous concept into something tangible that can make a real difference in your life. It beats the hell out of obsessing over replacing your light bulbs with CFLs and keeping your tires properly inflated, too.

Once you’ve bought a first house, buying a second is surprisingly doable. And relatively easy to achieve if, as we’ve been saying since we learned how to talk, you buy assets and sell liabilities. It’s all in here.