Why would you invest in a bond fund? It sounds like the most conservative of investments.

It isn’t. Bond funds, like the bonds they’re comprised of, offer yields that most stocks and mutual funds don’t. Bond funds can be volatile.

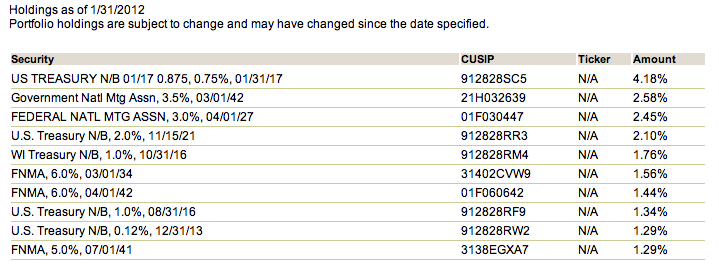

We examined the composition of the Wells Fargo Advantage Total Return Bond Fund (ticker symbol MNTRX), one of the biggest (if not the biggest) bond funds in existence. Here’s what it’s invested in:

That lists the fund’s 10 largest components, leaving 80% of the fund unaccounted for. So what’s missing?

Scroll to the bottom and in a tiny font it says “Click here for more complete holdings.” The hyperlinked part of the copy (“Click here”) isn’t even recognizable as a hyperlink.

How many bonds does MNTRX has a piece of? One Control Your Cash author guessed 50.

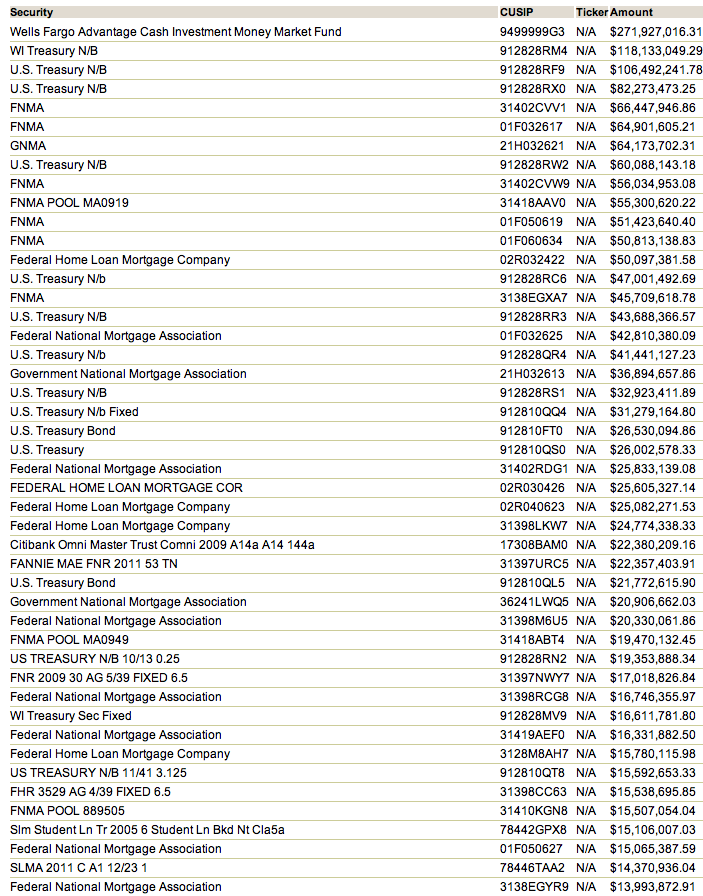

It holds 569. That’s not every bond in existence, but it’s plenty. We can’t fit the entire list on one page, nor would you want to read it, but here’s as much as we could cram into one screen cap.

If you can’t be bothered to look through all 569 components, this summary breaks them down by sector and grade.

The bonds typically pay interest quarterly, so there’s always money going in and coming out, thus the fund has to have cash reserves, therefore MNTRX’s primary component is a money market fund with readily accessible cash. (The rare “so/thus/therefore” hat trick.) Understandably, that money market fund is a Wells Fargo security too.

What about the actual bond components of MNTRX? First, notice how many U.S. Treasurys are on there. Makes sense, seeing as those are the only investments “backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government,” to the extent that that phrase still means anything.

But that’s only a small part of the story. The top 22 bond components include:

- 9 Fannie Mae

- 6 U.S. Treasury

- 3 Ginnie Mae

- 2 Freddie Mac

Not long ago we explained as best we could how Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are hundreds of times more rapacious than an entire investment bank full of Bernie Madoffs could ever be. Also, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac investments come with no explicit governmental guarantee. So why would Wells Fargo, a profit-seeking company, invest in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac bonds?

Because the ruse that they’re not backed by the government (and thus, you) is laughable. For all practical purposes, when the so-called “government-sponsored enterprises” run low on funds, the Department of the Treasury bankrolls them to whatever extent they can get away with.

Go to the second item in the list of components. The simple designation “FNMA” tells you little about the particular bond that the Wells Fargo fund is invested in. You have to look at the next column over, which contains a 9-character string called the CUSIP (Committee on Uniform Security Identification Procedures) number.

The first 6 digits of a CUSIP number tell you who the issuer is, the following 2 what type of security it is (debt or equity). The final digit is a check digit. There are a handful of online indices that let you search for a CUSIP, but they’re all either incomplete or they cost money. Your best bet is to just Google the CUSIP. Oh, is that too inconvenient for you? 20 years ago you’d have had to go to a broker’s office and look it up in a book. The second item on the list of components, 912828RM4, is listed as

U.S. Treasury Note, coupon rate of 1%, maturing October 31, 2016.

We’ll do the next 8, too:

912828RF9

U.S. Treasury Note, coupon rate of 1%, maturing August 31, 2016.

The only difference between the two is the maturity date. They each pay semiannually, and they’re each rated AAA.

912828RX0

U.S. Treasury Note, coupon rate of ⅞%, maturing December 31, 2016.

31402CVV1

Fannie Mae bond with a 6% pass-through rate, maturing March 1, 2034.

“Pass-through” rate means what the bond pays after the issuing agency takes its cut.

01F032617

Fannie Mae bond, 30-year term, 3½% coupon, 30-year term.

We can do this all day, but what does it mean?

In 2012, if you’re investing in a bond fund it’s because you want a higher return than you’d get from a certificate of deposit. You have to go all the way down to the 28th item on the list before finding a true corporate bond, that one being from Citibank’s Omni Master Trust series.

A whole bunch of federal government debt, interspersed with a handful of Extended Stay America and Bank of Montreal bonds. Does that mean that anyone with a list of bonds and a list of criteria could create a bond fund comparable to this one from Wells Fargo? Possibly.

Bond yields are extremely low right now. The yield on a 5-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Security is -.94%. Yes, negative. That’s more a function of the (steep) price it last traded at, than of how long it’ll take to mature. (10-year TIPS yield a slightly more rewarding .40%.) This is what happens when the Fed sets rates artificially low, essentially 0 for an extended period. You buy a bond with a negative yield when you’re anticipating that inflation will come, but hard. Keep in mind, we’re talking specifically about TIPS. Other treasurys don’t protect you against inflation. Nor do they protect you against deflation: should that happen, a TIPS will pay you the face value at maturity.

Oh yeah, the price. You can buy a share of MNTRX for $12.96 right now, which is almost the $13.10 it’s peaked at multiple times in the last couple of years. MNTRX debuted in 1997 at $12, and has never fallen below the $11.05 it sank to in 2000. A safer investment with less variance than a stock? Yes. A way to get rich? Probably not, unless the economy at large goes Greek. But a bond fund is a way to preserve your wealth while saving yourself from the risk of only having a couple of bonds in your portfolio and having them underperform. Unlike a bond itself, you can sell your position in a bond fund almost whenever you want.

This article is featured in:

**The Carnival of Personal Finance #350: The Little Prince’s Journey to Financial Enlightenment**